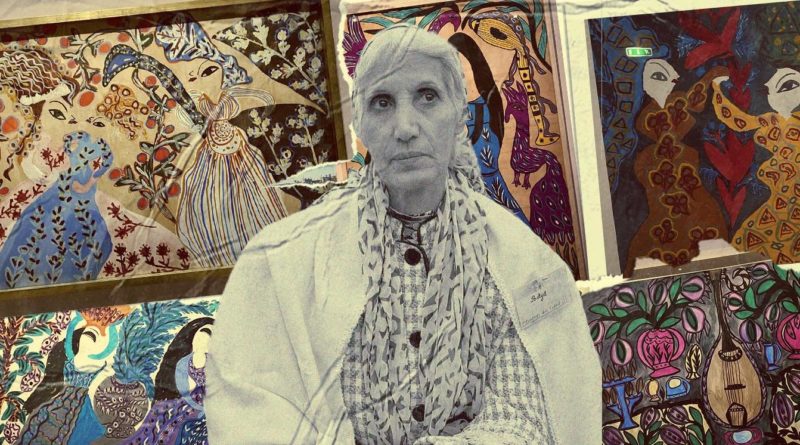

The Algerian pioneering artist few people know

Baya Mahieddine, a pioneering Algerian artist, played a significant role in the advancement of modern art in her country. She was born as Fatma Haddad in 1931 in Bordj el-Kiffan, a coastal town near Algiers, where her surroundings, including her upbringing in a traditional Muslim household and the vibrant colors and shapes of Algeria’s natural environment, influenced her work.

Baya began drawing and painting from a young age, using the materials she found around her home. Her early work featured vivid colors and fluid lines, depicting images of nature, animals, and women. Despite lacking formal artistic training, Baya’s unique style quickly gained recognition and praise from prominent artists and critics of the time.

Her paintings involved repetition with key elements, such as women’s wide skirts covered with amorphous animal shapes and musical instruments inspired by her husband’s Andalusian musical ensemble, which he often practiced in the courtyard. Although her drawings may seem repetitive at first glance, sophistication developed over the years. Baya was relaxed about her work and denied being influenced by symbols or patterns of the Kabyle, a Berber ethnic tribe indigenous to northern Algeria.

Baya’s work often challenged traditional gender roles and norms in Algerian society by portraying women as strong, independent figures rather than passive objects. Her bold use of color and form also reflected her desire to break free from the constraints of traditional art and express herself in a way that was true to her own experiences and vision.

In 1947, Baya caught the attention of French artist and critic André Breton while he was visiting Algiers. Breton was struck by her work and invited her to exhibit in Paris, where she quickly gained international recognition. Her work was exhibited alongside other prominent artists of the time, such as Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró.

Following her marriage to musician El Hadj Mahfoud Mahieddine in 1953, Baya embraced a more conventional Algerian Muslim way of life (Pélégri, 1987, p. 12). She relocated to Blida with her husband and started a family, eventually having six children. During this period of early marriage and motherhood, Baya took a hiatus from her art. While critics can only speculate on the reason behind this decision, it is notable that the decade in which Baya ceased painting coincides with the Algerian war for independence.

Baya’s success in Paris was a turning point in her career, establishing her as a leading figure in the development of modern art in Algeria. Her work continued to evolve throughout her career, incorporating new styles and techniques while maintaining her signature use of bold colors and forms.

Despite her international success, Baya remained connected to her roots and drew inspiration from Algerian culture and traditions. Her work reflected her belief in the importance of preserving and celebrating her country’s unique cultural heritage.

Baya passed away in 1998, but her legacy continues to inspire artists and art lovers worldwide. Her contributions to the development of modern art in Algeria and her commitment to breaking down barriers and challenging traditional gender roles have cemented her place in art history as a pioneering figure in the field.

Her paintinsg are celebrated even today. This month, the “L’institut du Monde Arab” is featuring her paintings in an exposition in Paris.