The ancient Amazigh script puzzling scientists

In the 19th century, French archaeologist Louis Félicien de Saulcy discovered mysterious writing resembling Sumerian on rocks in some Maghreb regions. He named it the “Numidian language” and the script became known as “Libyco-Tifinagh.” However, for 400 years, archaeologists and linguists have been unable to decipher this language of the ancient Amazighs. Libyco-Berber, accompanied by Egyptian hieroglyphs, is one of the oldest written languages in Africa and represents the most exciting and challenging topic in the history of North Africa.

Similar dicoveries were uncovered in many places across north african including Algerian regions, most notably in the cities of Souk ahras and Constantine. Similar writing are also reported in Morocco near the city of Settat.

Origin of Libyco-Berber

It is widely believed that the descendants of the Numidian people in North Africa use an alphabet inspired by Libyan: Tifinagh. The written character has preserved its origins, which date back hundreds of years. There are three theories about the origin of Libyco-Berber.

The first suggests that the alphabet and the principles of writing adopted by it are borrowed from the Phoenician script. The second theory sees that the language is derived from a historical stock of signs circulating in tattoos, geometric rock art, and others.

Finally, there is a third proposal that mixes the two theories, and it is believed that there are elements borrowed from Phoenician writing mixed with local symbols.

Libyco-Berber in North Africa

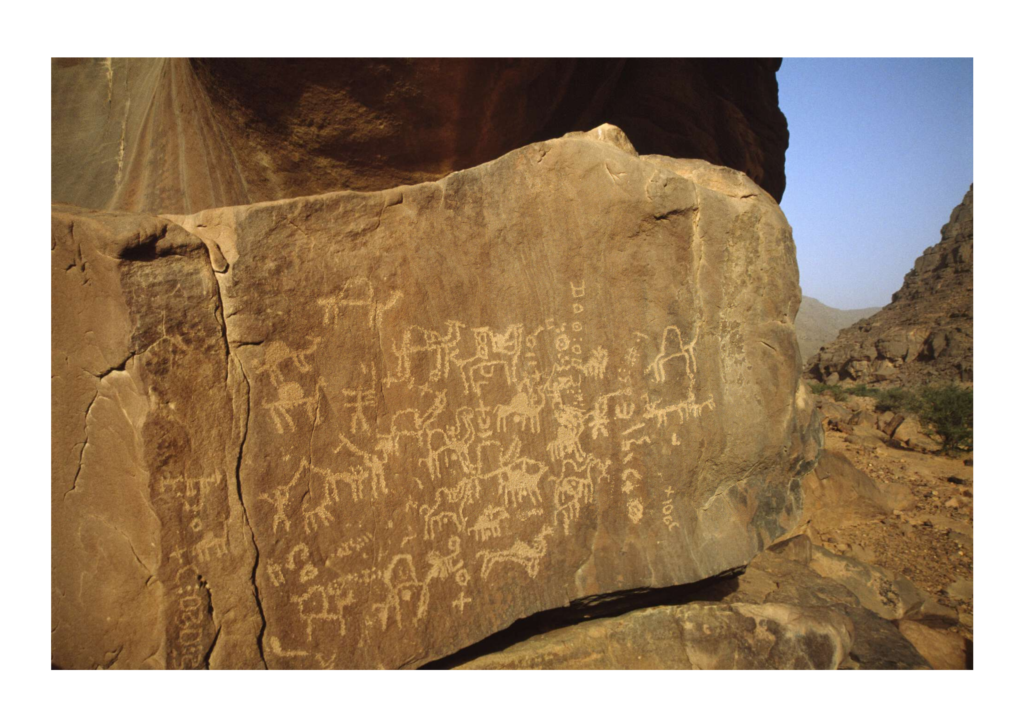

According to the British Museum, Libyco-Berber appears in “two different forms, either inscribed on paintings (mainly on the Mediterranean coast and remote areas) or on rock faces, either isolated or combined with paintings on the rocks.”

Some historical research confirms that the Libyan writing, which became a kind of rock art, was different from each other in drawings and form, due to geographical differences in the areas where it was discovered since the nineteenth century.

Oral versus Written Culture

French sociologist and anthropologist Pierre Bourdieu believed that Amazigh society is oral, and that it is oral traditions that play a pivotal role in the transmission of values, knowledge and cultural practices within Amazigh communities. However, the historical discoveries consistently show that the Amazigh regions of North Africa have been using the Libyan for almost a thousand years.

Vance Smith, a professor of the Middle Ages at Princeton University, wrote an article about the spread of writing on the African continent, pointing to Libyco-Berber as evidence that Africans also write. He noted that even supporters of Amazigh culture still categorize Africans incorrectly, and insist on the oral character of the Amazigh peoples.